Abstract. This paper analyzes current problems with the use of tactical airborne troops during operations (combat operations) due to the development of military assets and changes in the nature and content of modern military conflicts. It offers some possible solutions as a basis for further scientific research and discussion on this topic.

As the history of wars and armed conflicts testifies, one of the most important driving forces of military art is the equipping of troops with new military assets. For example, the fielding of helicopters by the Soviet Army in the mid-1960s contributed to the further development of the deep offensive operation, providing for simultaneous suppression of the enemy defense in its entire depth, the breakthrough of its tactical zone in the chosen direction, followed by the rapid transformation of tactical success into operational success through the battlefield deployment of the exploiting force (tank and motorized infantry formations, groupings) and airborne troops.

The scale of the use of landing forces has also steadily increased. For example, during the Zapad-81 major maneuvers, it was planned to land 166 airborne assault groups of varying numbers behind enemy lines, most of which (about 120) were tactical airborne assault forces as part of reinforced motorized infantry units.

At the current stage of military development, the urgency of increasing the mobility of troops and ensuring the rapid transfer and concentration of efforts in selected areas has increased even more, as evidenced by the results of the experiment to create airborne assault formations of a new type and their priority introduction into the structure of the Airborne Troops.1,2

At the same time, the use of tactical airborne assault forces as elements of the combat order of motorized infantry divisions (brigades) and the operational structure of combined-arms armies (groupings of troops in operational areas) for various objective and subjective reasons is gradually losing its importance, primarily due to the limited opportunities to create favorable conditions for realizing their combat potential.

It should be noted that the theory and practice of the combat use of tactical airborne assault troops, established in the 1970s and 1980s, have not changed significantly over the years. The changes were mainly confined to improving the way they carried out combat missions behind enemy lines, as well as to searching for and mastering new tactical techniques for joint operations with and on helicopters. There was lively discussion among military scientists on this topic that intensified after the publication in Military Thought of an article by A.V. Zelenov on the problem of airborne assault operations in modern military conflicts.3

Dialogue participants drew attention to the need to transform traditional (classic, typical) approaches to the combat use of airborne troops amid the changing conditions of armed conflict, especially in urbanized areas of the European theater of military operations, where the tactical defense zone of a potential enemy is saturated with modern reconnaissance and destruction assets, especially unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), missile defense weapon systems, including portable air defense systems, missile strike systems, and artillery using high-precision munitions.4 This refers, in particular, to the need to proactively identify the enemy’s vulnerabilities, gain temporary advantages in various areas, and develop and consolidate success by building up and/or transferring efforts, which are the essence of achieving superiority over the enemy on the battlefield in the current environment, the driving force of which is the effective use of military assets.5

In this regard, we believe that the typical principles of using tactical airborne troops require a substantial transformation of their essence, content, and the conditions of their implementation. We mean such principles as a sudden landing according to an integrated plan in the direction of the main strike with decisive goals and important missions that cannot be accomplished by other military formations; the reliable defeat of enemy air defense assets and troops in the interests of the landing; the organization and maintenance of close interaction with the forces and assets involved in support and cover, including with the formations advancing from the front; as well as the provision of comprehensive support for its operations, since the effectiveness of the enemy’s reconnaissance and defenses has greatly increased, and most of the opposition has been concentrated in urban agglomerations (urbanized enclaves).

Difficulties in organizing and using tactical airborne assault forces are also due to the presence of different scientific and practical approaches to gaining air superiority, which involve taking into account various indicators (in particular, the ratio of forces between the parties’ aircraft and the degree of destruction (suppression) of radio and radar stations, surveillance-and-attack and reconnaissance-and-fire systems, air defense systems, and enemy control points in the landing zone and on the nearest approaches), decreasing the intensity of enemy aviation and air defense systems, disrupting their control, deceiving the enemy about the intentions of the attacking party, and some others, whose measurement criteria are also different.6

In addition, under modern conditions, there are other aspects that make tactical airborne operations very problematic – namely, the implementation of measures and actions to conceal the preparation of landing troops; the mass delivery of materiel by helicopter to enemy rear areas, especially combat vehicles and towed artillery; and the reliable destruction of the enemy in the flight zone and the nearest approaches to it before the landing. Other things also require revision: indicators for the use of tactical airborne troops and their composition; norms for allocating airlift vehicles (helicopters); the procedure for forming combat ranks and distributing weapons; and the content and methods of carrying out combat missions, including tactical techniques for using the new weapons and military equipment.

Let us consider in more detail the influence of modern conditions and factors on the use of tactical airborne assault troops and existing problems and possible ways to solve them based on the stages of their preparation, landing, and performance of assigned combat missions in the enemy’s rear area.

Work on organizing the use of tactical airborne assault troops begins when the command body of the relevant military unit, after understanding the mission and assessing the emerging situation, perceives the need to create this element of the operational structure (combat order).

Under the provisions of modern military art theory, airborne tactical forces are intended to build up efforts in the direction of the main strike in order to help troops defeat the opposing enemy and achieve a high tempo of the offensive, as well as to prevent (complicate) the maneuvering of the enemy’s reserves and disrupt the control of his troops and weapons and the work of the rear. Tactical airborne troops may be assigned the following main tasks: capturing and holding important bases (facilities); destroying (disabling) ground elements of enemy reconnaissance-and-fire and surveillance-and-attack systems and command and control centers; destroying enemy rear formations; disabling communications; capturing and maintaining airfields; etc. Based on this and considering the enemy’s capabilities to counter airborne assaults, the composition of tactical airborne assault troops and the assets that ensure their successful application are determined.

The presented classic [scenario] is currently acceptable as an element of a deep offensive operation, primarily in nonurbanized territories with significant operational areas that are accessible to troops. However, an analysis of the experience of military conflicts in recent decades in densely populated areas of Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East gives grounds to assert that the main confrontation of forces and, accordingly, the efforts of the opposing sides occur and are concentrated in urban agglomerations and urbanized enclaves, with reliance on the infrastructure and operational equipment of the territory, often using the civilian population as a human shield.

The critical importance of most of this infrastructure and equipment is determined by the fact that their destruction during capture significantly reduces the safety of the population, which virtually eliminates the possibility of powerful fire impact on them. The passage through agglomerations of transport lines with road junctions – i.e., supply, evacuation, and maneuvering routes – only exacerbates the situation.

Therefore, the timely arrival of troops advancing from the front to join a tactical airborne assault unit is significantly more difficult and unpredictable, which limits the ability of the landing force to retain important terrain elements and operational equipment behind enemy lines.

At the same time, under modern conditions, critical facilities behind enemy lines are sufficiently destroyed (disabled) by long-range precision-guided air, ground, and sea-based weapons, so in our view, using tactical airborne assault troops to do this seems inexpedient. Under this approach, the list of missions for tactical airborne assault troops that cannot be performed by other resources and capabilities should become more limited and functional.

The composition of the tactical airborne assault unit also needs to be revised. At present, it usually consists of a reinforced motorized rifle battalion (company) from a combined arms unit (formation) or airborne assault unit under their operational command using standard equipment. They are generally assigned reconnaissance and electronic warfare units, self-propelled or towed artillery and antiaircraft units, flamethrowers and sappers, as well as a UAV crew and an air observer.

Transporting such units behind enemy lines with standard equipment and combat gear placed inside cargo bays and on the external sling of transport helicopters requires significant Army aviation resources while reducing the flight range at the expense of maximum load. If tactical airborne assault troops are used only with light portable weapons, they will have low firepower and maneuverability with a short duration of autonomous (independent) actions behind enemy lines.

In addition, troop transport helicopters (Mi-8MT, Mi-8AMTSh, and Mi-8MTV-5) usually can carry up to 1.5 platoons (24 to 36 people) with portable weapons (without crews and combat vehicles) and transport helicopters (Mi-26) can carry up to a company (82 people), which can lead to significant losses in flight due to limited capabilities to penetrate and suppress enemy air defense systems operating in passive mode, especially MANPADS.

The most realistic way to solve this problem is to significantly reduce the number of paratroopers transported on one flight (up to eight to 10 people), which, in turn, predetermines the need to expand the range of transport and combat helicopters through the creation and adoption of lightly armored helicopters with a carrying capacity of one squad (see Fig. 1).7

Fig. 1. Proposed lightly armored assault helicopter for one squad

This lightly armored helicopter is not suitable for open combat, but when equipped with a bow-mounted 30-mm automatic gun, two 7.62-mm and two 12.7-mm machine guns, as well as sets of unguided and guided antitank missiles, it can be successfully used as an air gunner or airmobile combat vehicle. The technology of folding the rotors into a case on top of the helicopter body with their subsequent unfolding facilitates their concealed transportation by contractors to the launching area in a container by both road and rail transport, which has shown its relevance during the special military operation in Ukraine.

Another major problem is the inability of the organizational bodies of military formations assigned to tactical airborne assault formations to adjust to performing their specific missions. For example, units allocated to tactical airborne assaults from combined arms formations have limited capabilities to create complete elements of the combat order and use standard weapons and military equipment, and the involvement of airborne assault units requires a fairly long period of coordination, which does not always permit a prompt response to sudden changes in the situation.

As a solution to this problem, it is advisable to turn to the experience of combat operations in Afghanistan, when individual combined arms formations or their reconnaissance battalions included airborne assault battalions and, accordingly, reconnaissance airborne assault companies. When implementing such a solution, these units should be equipped with weapons and military equipment adapted to the specifics of tactical airborne assault units.

As for the armament of tactical airborne assault troops, first of all, it should be noted that, after landing, paratroopers have to carry a significant load of ammunition, supplies, and equipment, and this reduces the speed and maneuverability of the unit as a whole. During an experiment to create a new type of airborne assault unit in the airborne troops, the possibility of using quad bikes and buggies of various modifications for these purposes was tested. However, it turned out that they do not fully meet the needs for carrying capacity, cross-country ability, and firepower, and the mass and dimensions of special vehicles based on the Typhoon-VDV chassis are too large.

In this connection, we think it is necessary to develop a line of unembellished all-wheel drive off-road container-type transporters with increased load capacity per squad (crew) capable of transporting platoon and company ammunition, small arms, grenade launchers, antitank missile systems, 82 mm mortars and other weapons, as well as communication, camouflage, food, fuel, and other assets. It is important that they have a remote-control function and that their dimensional characteristics make them air transportable. Of course, in some environments, such as steppes and foothills, high-speed buggies can be very useful for blocking illegal armed groups, but tactical airborne assault units still need off-road transporters (see Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Proposed off-road transporter models for a squad

At the same time, it is advisable to equip units designed to conduct tactical airborne assault operations with loitering munitions, UAVs of various purposes and countermeasures, correctable and guided munitions for artillery, homing devices, reconnaissance (recognition) and target designation systems, detection stations, protected communications equipment, and other effective weapons and military equipment.

To prepare tactical airborne assault forces for use, a launching area is assigned, and in accordance with current recommendations, the distance from the line of contact is 20 to 30 km in a formation and 50 to 70 km in a large unit (army). However, the experience of the special military operation in Ukraine has shown that the enemy’s ability to conduct reconnaissance and launch high-precision strikes, taking into account NATO supplies of self-propelled (M109) and towed (M777ER) howitzers and multiple rocket launchers (R142HIMARS), has increased significantly and exceeds 70 km. In this regard, in the operational structure and combat orders of the troops (forces), there is an obvious need to clarify the the distance of launching areas for tactical airborne assault troops, taking into account their coverage in the general air defense system.

According to the existing classics of military art, tactical airborne assaults are used after the main forces have accomplished the immediate mission (breakthrough of the tactical defense zone), when there are gaps in the enemy’s combat formations, and the conditions exist to ramp up efforts by introducing second echelons (reserves) into battle, or later, but only if troops are maintaining a steady attack pace.

However, a study of the experience of the special military operation in Ukraine has shown that it is sometimes advisable to land tactical airborne assault units at the beginning of an offensive to achieve the element of surprise, but only if they will be joined by bypass (raiding) detachments with armored groups assigned to the airborne assault unit introduced into combat at the start of the operation through tactical discontinuities in the enemy’s combat orders and moving to bypass its main resistance nodes.

There are also many questions about the ability to reliably hit enemy air defense assets, as well as elements of enemy troop and weapon control systems in the interests of a tactical airborne assault in the army aviation flight zone and the nearest approaches to it ahead of the landing flight. When the enemy tactical defense zone is saturated with MANPADs and antiaircraft artillery, these capabilities, primarily to detect their positions, are very limited. Moreover, it is rather difficult to organize the simultaneous involvement of a considerable part of missile troops and artillery; electronic warfare; and attack, fighter, and bomber aviation to attack them shortly before the tactical airborne assault unit takes off. In addition, there is the possibility that the enemy could restore the combat effectiveness of most defeated and suppressed air defense forces and assets before the arrival of army aviation with the main landing force.

US Army Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore, a Vietnam War veteran, wrote in his memoirs about the complexity of this task and the scale of the resources involved. According to him, the artillery of the 1st Cavalry Division spent 33,000 105 mm shells to support a battalion landed as an airborne assault force during the Battle of the Ya Drang (Drang River) Valleyin 1965 in South Vietnam.8

In our opinion, this problem can be solved based on the creative development of the theory of complex impact on the enemy in operations, having provided for the systematic use of reconnaissance, destruction, and defense assets in all areas of confrontation, as well as by creating a joint-force automated reconnaissance and strike system.

Once tactical airborne assault troops have been prepared for use, they are airlifted to the rear of the enemy; this includes the take-off of landing helicopters, the formation of their airborne combat order, their flight, and the landing of units in the landing area. Without talking about the tactics used by army aviation during the flight, we should note the low survivability of helicopters, especially due to the enemy’s use of MANPADs, as well as of the paratroopers themselves before dispersing the units and beginning their support by standard artillery and air defense means.

The presence of MANPADs allows the enemy to attack low-altitude aerial targets at ranges of several kilometers, making them a convenient means of defending troops against air strikes. Infrared countermeasures (decoys) are currently considered the primary method of defense against MANPADS. However, the latest surface-to-air missiles are able to distinguish helicopter engine temperature and exhaust fumes from the decoy, and some of them even select targets based on several parameters at once.

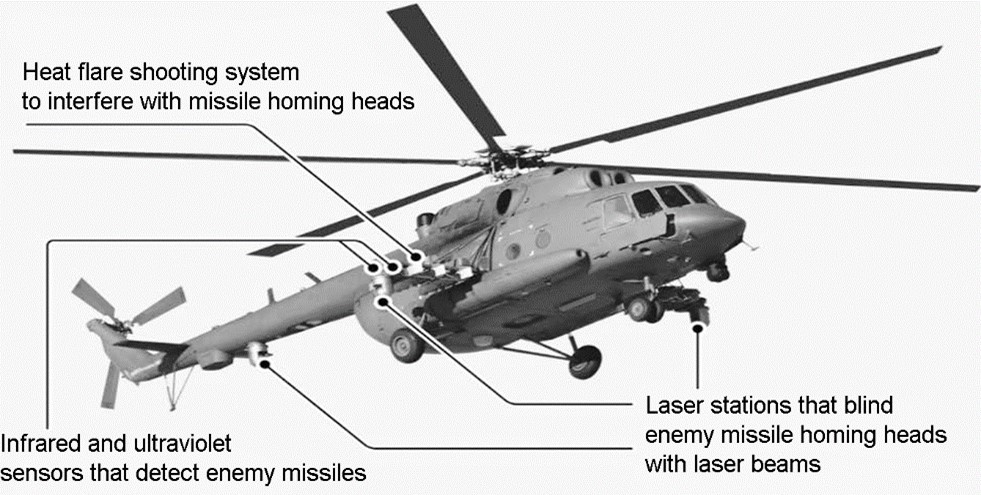

Therefore, to protect helicopters from enemy air defense assets (search, suppression, and disruption of attacks), it is necessary to develop and install special equipment on them – in particular, devices that make it possible to timely warn the crew of radar and laser irradiation, create active interference, perform optical-electronic (laser) suppression (blinding) of homing heads of anti-aircraft missiles (see Fig. 3), and also mount screen protectors.

Fig. 3. President-C airborne defense system on a Mi-8AMTSh helicopter

In addition, it is advisable to include a surveillance-and-attack group consisting of UAVs with various equipment and air targets identical in their parameters to an Mi-8 helicopter, as well as loitering munitions in the combat order of army aviation when flying to perform an airborne landing. In general, to detect an enemy air defense system in advance of the landing, an Orlan-10 UAV with a universal load should be planned for a group aerial photography sortie in radio silence mode to a depth of more than 100 km.

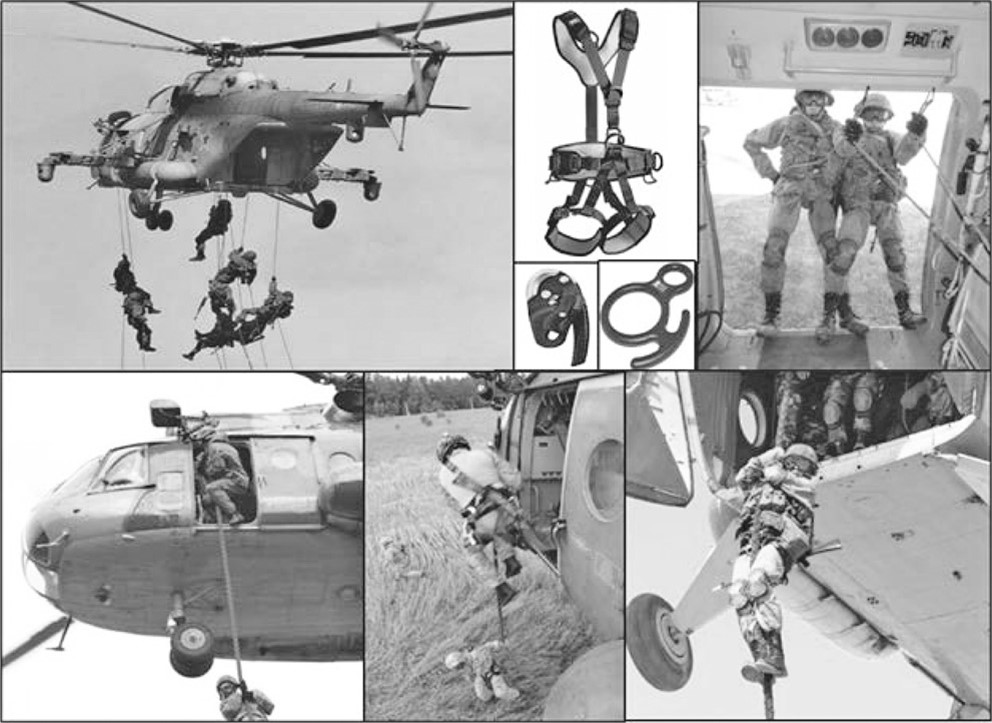

The difficulty of landing troops directly at the object to be captured while restoring the combat effectiveness of most of its covering, protection, and defense forces requires searching for and implementing unconventional approaches to determining the composition of forces and equipment of follow-on reconnaissance groups and advance units that are sent ahead of the main tactical airborne assault forces along the flight path; the places where they will land; means of suppressing enemy air defense, protection, and defense assets; as well as landing sites. In our opinion, the most acceptable in this regard may be the developed rappelling methods of the advanced airborne group using rappelling devices (ropes) and special cables without landing helicopters on the ground (see Fig. 4),9 which will facilitate the timely creation of elements of the support strip to limit the actions of the nearest enemy reserves on approaches to the landing area of the main forces of the tactical airborne assault.

The typical method of carrying out tactical airborne assault missions behind enemy lines is to engage the enemy and then attack the main forces from several directions supported by artillery fire with the simultaneous (advance) allocation of some forces for cover, as well as to strike enemy reserves with air and missile strikes. A major problem is the low survivability of the landing troops in the limited landing area and during the mission because of likely intense artillery fire and enemy air strikes, including those that are beyond the range of the tactical airborne assault troops’ weapons.

Fig. 4. Disembarking of landing troops using descent devices and ropes

In our opinion, the following measures and actions can increase the survivability of tactical airborne assault troops in the landing area and when performing missions behind enemy lines:

· developing and implementing techniques for the integrated use of UAVs of various types with various payloads, as well as of loitering munitions for reconnaissance and defeat of the enemy at the approaches to the area held by the airborne landing unit, including in cooperation with electronic warfare assets and artillery

· optimizing the combined arms formations created at command posts that use tactical airborne assaults, as well as air reconnaissance and weapons fire command and control bodies

· developing methods to create a support strip (enemy access restriction zone) on the approaches to the main tactical airborne assault defense area (at least to the depth of detailed reconnaissance), including through the remote installation of mine (antipersonnel, antitank, and antihelicopter) obstacles and jamming transmitters

· improving the methods of action of mobile fire groups and mobile fire units, the stealth of forces and assets of tactical airborne assault troops both at the approaches to the front line and in the area of defense of its main forces

· improving the effectiveness of tactical airborne assault control systems and general military formations, using them on the basis of promising defense industry developments and proposals to ensure interference-resistant all with all information exchange under any physical and geographical conditions

· automating artillery fire, air defense, and air strikes control processes

· uniting all control points, unit commanders of all links, service personnel, and helicopter crews based on a single data transfer system.

Implementing these measures will significantly improve the survivability of tactical airborne assault forces by preempting the enemy in implementing the control cycle of troops (forces) and weapons through information, technological, and technical advantages over him, and also improve the effective integrated defeat of enemy systems and weapons while ensuring the safety of friendly units and materiel. This creates favorable conditions for the highly effective actions (realization of potential capabilities) of tactical airborne assault troops with the least losses and time, labor, and material costs (resource intensity).

In conclusion, it should be noted that the presence of a significant number of pressing and acute problems requiring urgent solutions regarding the use of tactical airborne assault troops in modern military conflicts makes it advisable to consider it a specific type of action of combined arms formations requiring the creation of special conditions for achieving success with minimal losses. This, in turn, makes it necessary to conduct further thorough research on this topic and continue relevant scientific discussions, including on the pages of Military Thought.

NOTES:

1.A.N. Serdyukov, “‘V sostave VDV poyavlyayutsya shturmoviye soyedineniya novogo tipa’. Komanduyushchiy Vozdushno-desantnymi voyskami general-polkovnik Andrey Serdyukov – o reformakh v krylatoy pekhote i perspektivnom vooruzheniyi [Assault formations of a new type are appearing the Airborne Forces. Commander of the Airborne Troops, Col. Gen. Andrey Serdyukov on reforms in the airborne infantry and on advanced weapons].” Izvestiya, December 18, 2020.

2. Vintokrylaya pekhota: v VDV pristupili k sozdaniyu batal’onov novogo tipa [Rotary-winged infantry: the Airborne Forces began to create a new type of battalion]. Izvestiya, February 24, 2021. URL: https://iz.ru/1128589/roman-kretcul-aleksei-ramm/vintokrylaia-pekhota-v-vdv-pristupili-k-sozdaniiu-batalonov-novogo-tipa (Retrieved on January 10, 2023.)

3.A.V. Zelenov, “Desantno-shturmoviye deystviya v sovremennom voyennom konflikte i perspektiva ikh razvitiya [Airborne assault operations in modern military conflicts and the prospect of their development].” Voyennaya Mysl’, # 6, 2021, pp. 28-35.

4.Sovremenniy rossiyskiy vzglyad na desantno-shturmoviye deystviya [The modern Russian view on air assault actions]. URL: https://rostislavddd.livejournal.com/445804.html (Retrieved on January 12, 2023.)

5.A.V. Vdovin, Teoreticheskiye osnovy dostizheniya prevoskhodstva nad protivnikom v upravleniyi [Theoretical foundations for achieving superiority over the enemy in control]. Sbornik materialov voyenno-nauchnoy konferentsiyi. VUNTS SV “OVA VS RF,” Moscow, 2022, pp. 41-48.

6.A.V. Vdovin, Razvitiye teoriyi boyevogo primeneniya desantno-shturmovykh formirovaniy: monografiya [Development of the theory of combat use of air assault formations: a monograph]. VUNTS SV “OVA VS RF,” Moscow, 2017, 150 pp.

7.V.V. Gindrankov, “Gospodstvo v vozdukhe: mify i real’nost’ [Dominance in the air: myths and reality].” Voyennaya Mysl’, # 9, 2020, pp. 70-78.

8.H.G. Moore, We were soldiers once, and young. Random House, USA, 1992, 432 p.

9.Rukovodstvo po besparashutnomu desantirovaniyu (RBPD-2020) [Guide to Rappelling (GR-2020)]. Komandovaniye VDV, Moscow, 2020.