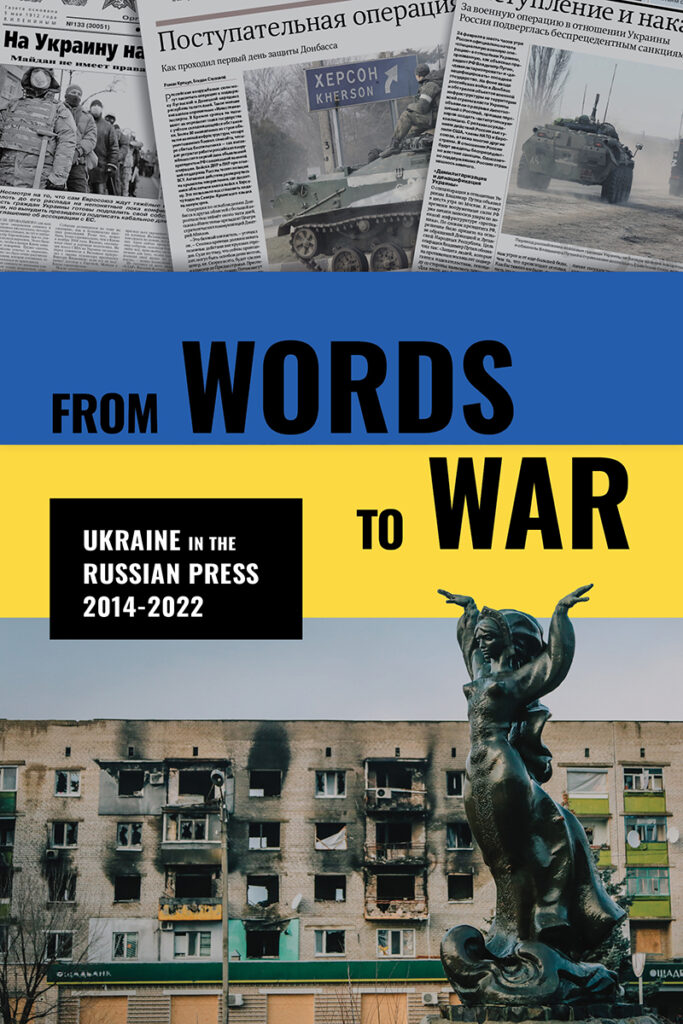

From Words to War Featured Excerpt

The following article is from Part One — From Maidan to Novorossia

THE SIEMENS INCIDENT: HOW RUSSIA IS LOSING ITS SOVEREIGNTY

By Sergei Medvedev, historian and journalist. Republic.ru. Aug. 4, 2017. https://republic.ru/posts/85621.

History repeats itself as farce. In 1999, after then [Russian] prime minister Yevgeny Primakov learned about [NATO] strikes against Yugoslavia, he made a regal gesture and gave an order to turn his plane around over the Atlantic, causing panic in world capitals. Eighteen years later, when an S7 plane carrying [Russian] Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin to Chisinau was ordered to make a U-turn over Romania and return to Minsk, it only drew laughter on social media, while the deputy prime minister, who wrote a menacing tweet – “Just you wait, scumbags” – later deleted it himself.

Given that Dmitry Rogozin is basically a clown, proposing things like building bases on the Moon or underwater cities in the Arctic, this episode could have remained a blip on the radar. However, [Rogozin’s] recent gaffe points to a far bigger problem facing Russia today: The rapid deterioration of its foreign policy sovereignty – how else can you describe a situation when a deputy prime minister cannot accomplish a mission in a neighboring country?

However, here is a far more serious problem: The controversy around Siemens turbines that were illegally shipped to the Crimea despite assurances from Vladimir Putin to the German leadership [that they would not be – Trans.]. The problem here is that due to European sanctions and Russia’s clumsy attempts to evade them, [Moscow] proved unable to supply electricity to a part of its strategic territory – in other words, this is about the erosion of energy sovereignty. Moreover, this clumsy attempt, in turn, has brought about new European sanctions.

Finally, there’s the recent package of US sanctions that Donald Trump signed on Aug. 2: Their scope and impact are not clear yet (Russia could lose up to one-third of its gas exports to Europe), but it’s obvious that they significantly limit Russia’s foreign policy and trade opportunities. Given the overall situation over the last three years, the sharply reduced room to maneuver [and] Russia’s political and reputational resources, it is clear that our country is steadily losing its sovereignty.

One recognized authority in political science on the theory of sovereignty is Stephen Krasner, an American. In his 1999 classic work “Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy” (an obvious reference to [Max] Weber’s definition of the state as “organized violence”), he specifies four aspects of sovereignty in international relations: legal sovereignty (the legal recognition of states within their borders); Westphalian sovereignty (states determine their own domestic authority); domestic sovereignty (national authorities have effective control within the same borders) and interdependence sovereignty – i.e., the ability to pursue a policy with regard to transborder flows of information, people, ideas, goods and threats. A look at the policies of Putin’s Russia shows that it just barely meets the first two requirements: It has UN recognition (although without the Crimea) and managed to banish “foreign agents” from domestic politics. At the same time, the ruling regime’s ability to exercise control over domestic processes, let alone integrate into globalization, has been greatly weakened.

The problem of the Russian political class is that it thinks in exclusively retrograde terms: It wistfully sees international politics within the framework of some sort of new Yalta [agreement] or even a new Vienna Congress, and [it views] domestic politics even more regressively – within the framework of Westphalia (the 1648 Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years’ War and for the first time recognized states as sovereign subjects within their borders). It does not want to face up to the fact that “Westphalia” ended long ago [and] states do not control global flows; they share powers with transnational organizations. It is no accident that Krasner describes absolute sovereignty as “hypocrisy” and compares it to Swiss cheese with big holes.

However, if we take even the most basic meaning of the word “sovereignty” from any political dictionary, it means the state’s independence in its domestic and foreign policy. But how can you talk about independence when Russia is dependent on Siemens for energy supplies to the Crimea and on Romania – for the deputy prime minister’s flight to Moldova? [It is] dependent on the US in its foreign policy and on Ukraine in its domestic agenda. As a matter of fact, Russia’s foreign policy is nothing but an excruciating, complex, Freudian or Dostoyevskian dialogue with America about spheres of influence, superpower status and ambitions – a dialogue that constantly turns into a monologue about Russia’s wounded pride. The sheer obsession of the Russian ruling establishment with US elections, the childishly naïve struggle with Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, then a vaudeville romance with Donald Trump, its bull-in-a-china-shop attempts to meddle in elections, [Russian Prime Minister] Dmitry Medvedev’s recent despairing tweet with regard to Trump’s “humiliating” handover of power to Congress – all of these are signs of hopeless, pathological and psychological dependence on the “Washington apparatchiks.”

Likewise, Russia is dependent on a fragment of the empire that has sailed away – Ukraine, building its entire foreign and domestic agenda on demonizing the Maidan uprising and filling its airwaves with an endless Ukraine saga, displacing the Russian domestic agenda with a Ukrainian agenda. One gets the impression that if Ukraine suddenly weren’t there, Russia would cease to exist. All of this goes to show that Russia basically has no agenda of its own [and that] its policy is nothing but knee-jerk reactions to external irritants [and] an inability and a reluctance to accept the world as it is, acknowledging its dependence on the world. This reluctance is in fact the surest symptom of dependence.

To better understand its situation, the Kremlin should take a look at countries that have moved even farther down the path of sovereignty – Iran or, better yet, North Korea: Flaunting its absolute independence, that country is absolutely vulnerable. It’s under sanctions and under the constant threat of a military strike; it can hold on only by upping the ante in a mortal game of poker. Its sovereignty is hanging by the thin thread of a nuclear bluff and on trading in threats.

Ironically, the underlying cause of Russia’s current troubles is in fact a war for sovereignty, which became the basis of Putin’s conservative turn around 2003-2004. First, there was the expropriation of Yukos and the Beslan [2004 school hostage] crisis that Putin blamed on the West’s desire to grab “the juiciest bits”; then there was the strange creature called “sovereign democracy”; the [2007] Munich speech and Georgia; then came the Crimea, the Donetsk Basin, Novorossia, the fight against separatism and “foreign agents”; the destruction of banned peaches and plans to build a sovereign Internet. However, the more entrenched Russia got in the imaginary idea of “Westphalian” sovereignty, the more it lost actual sovereignty, along with an independent foreign policy, control over its economy and society [and] the ability to adapt to globalization.

The crucial mistake here was the annexation of the Crimea (precisely in accordance with the saying: “It’s worse than a crime, it’s a mistake”): It seemed that Russia was strengthening its sovereignty [and] beginning to gather its lands but in the end, this act radically undermined the nation’s independence. More than three years later, it is becoming evident that Russia is losing its technological sovereignty (ask oil producers who are unable to drill on the sovereign Arctic shelf without Western technology), its foreign policy sovereignty (once it switched to the mode of confrontation with the West, Russia narrowed its room to maneuver with each subsequent step it took until it came up against the wall of recent sanctions) and even domestic sovereignty. This is not even about power shortages in the Crimea or that the Russian Constitution does not apply to Chechnya but that, as Krasner put it, rulers often confuse authority with control, and while the vertical chain of command looks to be growing stronger, actual control over the economic and social situation in Russia is weakening every day. One of the main achievements of Putin’s rule that propaganda keeps boasting about – i.e., strengthening sovereignty – turned out to be a myth.

As a result, this adds up to the usual Russian story: No matter what parts you steal from a factory, you end up with a machine gun; no matter how hard you fight for sovereignty, only the ruling authority becomes stronger. Or maybe a stronger ruling authority was in fact the Kremlin’s only goal in the first place, while the push for sovereignty was just an ideological cover and a way to find legitimacy? However, this creates an inverse proportion: The more power the Kremlin has, the less sovereignty Russia has. In the end, it could be that all power will be concentrated in the Kremlin – a forbidden city, the emperor’s palace – while the rest of the country will be abandoned to its fate. This has happened before in Russian history, when in December 1565, Ivan the Terrible departed for the village of Kolomenskoye together with his court, the treasury, as well as icons and power symbols. He then moved on to the Aleksandrov Kremlin, where he founded his oprichnina. Essentially, the tsar took all power with him, leaving Russia to be plundered by Tatars, then the oprichnina, then – the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As a result, the country was deprived of its sovereignty for many years, until the Zemsky Sobor [Land Assembly] of 1613 and the start of the Romanov dynasty.

Sovereignty is not about a tsar’s convoy with icons, the president’s [annual] call-in show, or “polite [little green] men” in the Crimea. It’s not about military bases in the Arctic, displays of Topol [strategic missiles] on Red Square or a warship parade on Navy Day. It is about the government’s constant work to transform the country, integrate it into the rest of the world and have it recognized by this world. In this sense, the Siemens incident is a disturbing sign for Russia: A territory may be annexed, cleaned up, packed with arms and used as parade grounds, but sovereignty does not work without turbines or international recognition. The Crimea turned out to be the hole in the sovereignty cheese that Stephen Krasner writes about in his book.